The following is the preface to my new novel “High Wine” set in the latter part of the 1700s and early 1800s.

The principal character is a youth named Sicheii, a mixed-blood Native and rumoured son of Duncan McGillivray; one of three shareholders in the legendary North West Company.

PREFACE

Simon McTavish started life as a poor boy in 1751, and at the age of thirteen, he was sent to New York to apprentice with a Scots merchant. It was here that McTavish saw the opportunities in the fur trade business, and in 1772 he went to Detroit selling deer and muskrat hides. Profiting at this, he extended his operations to Grand Portage on Lake Superior, the rendezvous point for fur traders and trappers.

Although the Hudson’s Bay Company controlled the prime north-westerly areas for fur trapping, there was still a relatively lucrative route from Montreal westward via the Ottawa River and across Georgian Bay and the Great Lakes Region into Manitoba. Indeed, most of the trade at Grand Portage went through Montreal.

In 1775–76, McTavish had the great good fortune to winter at Detroit, and being well stocked with trade goods he made an expedition to the Great Lakes to barter for furs. Meanwhile, the U.S. Continental Army occupied Montreal – having taken it in 1775 – which prevented the Montreal traders from getting their goods to Grand Portage for the 1776 season. Thus McTavish, with little competition, was able to obtain furs which he valued at £15,000[1] and take them to England for sale in a high market.

In the meantime, the Americans had withdrawn from Quebec, and so McTavish transferred his operations to Montreal. He continued to trade on his own through the Revolutionary War, supplying goods both at Grand Portage and Detroit, and speculating in rum for the British soldiers at Detroit and Niagara Falls. Therefore, by the end of the war, he was able to put together a group of business investors and trapper/explorers to create the North West Company.

A restructuring of the company a few months later saw the shrewd McTavish gain control of eleven of the company’s twenty shares. Moreover, he was now managing partner of a new Montreal firm called McTavish, Frobisher and Company, which imported the North West Company’s goods and forwarded its furs to the London market, taking commissions on all transactions.

The vertical integration of the business was extended in 1792, when the firm of McTavish, Fraser and Company was established in London, England, to procure the trade goods at source and sell the furs. From his headquarters in Montreal, over the next sixteen years, McTavish built a business empire that stretched from the Labrador coast to the Rocky Mountains and in the process made himself a wealthy man.

It was about this time that he made a visit to the Old Country, and while he was there, he learned of the plight of his Sister Anne’s Family. She had married Donald Roy McGillivray, and together they had three sons.

The McGillivrays had traditionally held the Dunmaglass estate since the fourteenth century, and Donald’s father was a first cousin of the Chief of the Clan McGillivray of Dunmaglass. However, on his side of the family, the land had dissipated so that he was a small tenant on what had become part of the Lovat estate, and he was unable to provide secondary schooling for his boys, William, Duncan, and Simon. Therefore, McTavish undertook to pay for their education.

They were all very bright lads, and so McTavish brought the oldest, William, to Canada to apprentice with the North West Company at an annual salary of £100. Duncan and Simon also took their place within the company; however, since Simon had a lame foot, he remained in the United Kingdom to work for McTavish, Fraser and Company of London.

He eventually worked his way up until he had acquired the controlling interest in the company, and later became one of the owners of the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser. He also played an important role in the merger of the North West Company and its rival the Hudson’s Bay Company.

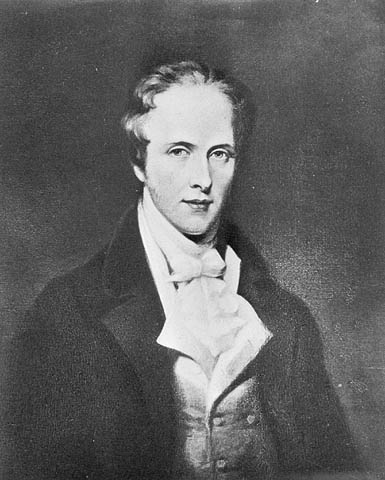

Duncan McGillivray was the most adventurous of the three. While brother William strategized as the controlling partner of the North West Company, Duncan revelled in the adventure of discovery as he crossed the country from Montreal to the Rocky Mountains and beyond, living the rugged life of both a Voyageur and Coureur de Bois.

While there is no record of a marriage, he is known to have taken a “Country Wife”[2] by the name of Margaaret Bean (an “American Indian”) with whom he had two children – Magdalene, born in 1801, and William, c. 1796. There is also the strong possibility of a third child named Sicheii (meaning “Son”) who unexpectedly arrived in Montreal in the care of a nurse and some voyageurs after his mother had died in 1806.

There was some question regarding his paternity because Duncan had already returned to Montreal before he was born; nonetheless, he took him in and arranged for his education until he died in 1808. Following this, his uncle William – no doubt remembering how his own uncle Simon had paid for his education – took over until Sicheii was ready to apprentice with the Northwest Company like his father and uncle before him.

The only question now was where the somewhat soft-spoken teenager with his large brown eyes and ebony locks would fit in, and so it was decided that Fort Kaministiquia (Fort William, on the north shore of Lake Superior) would suit for the time being.

Therefore, since there was a supply brigade

ready to leave from Lachine – about nine miles upriver from Montreal – Sicheii

was placed on it. Nonetheless, William quietly arranged for one of the

voyageurs – a Métis like Sicheii – to watch over him along the way.

[1] The value of £15,000 in 1775 is the equivalent of $33,720,000 USD in today’s dollars.

[2] Mariage à la façon du pays: “Marriage in the custom of the country.” Many unions occurred between European men and aboriginal women without European-based religious and legal ceremonies.

Discover Gerry Burnie’s all-Canadian adventures. Click on the images to learn more:

Post navigation

“Lord Selkirk’s Settlement”: A brief history of the Red River district, Manitoba

T

As it was, the ship didn’t set sail until July 26th with one hundred and twenty men on board, and with bad weather adding to the delay they didn’t arrive at York Factory on James Bay until September 24th, 1811. By this time, it was too late to make the trip south before freeze-up, and so they spent the winter hunting and building York Boats

As it was, the ship didn’t set sail until July 26th with one hundred and twenty men on board, and with bad weather adding to the delay they didn’t arrive at York Factory on James Bay until September 24th, 1811. By this time, it was too late to make the trip south before freeze-up, and so they spent the winter hunting and building York Boats